Driving Down Methane Leaks from the Oil and Gas Industry

A Regulatory Roadmap and Toolkit

About this report

Reducing methane emissions from oil and gas operations is among the most cost-effective and impactful actions that governments can take to achieve global climate goals. There is a major opportunity for countries looking to develop policies and regulations in this area to learn from the experience of jurisdictions that have already adopted methane-specific regulations in order to design frameworks that are adapted and tailored to local circumstances.

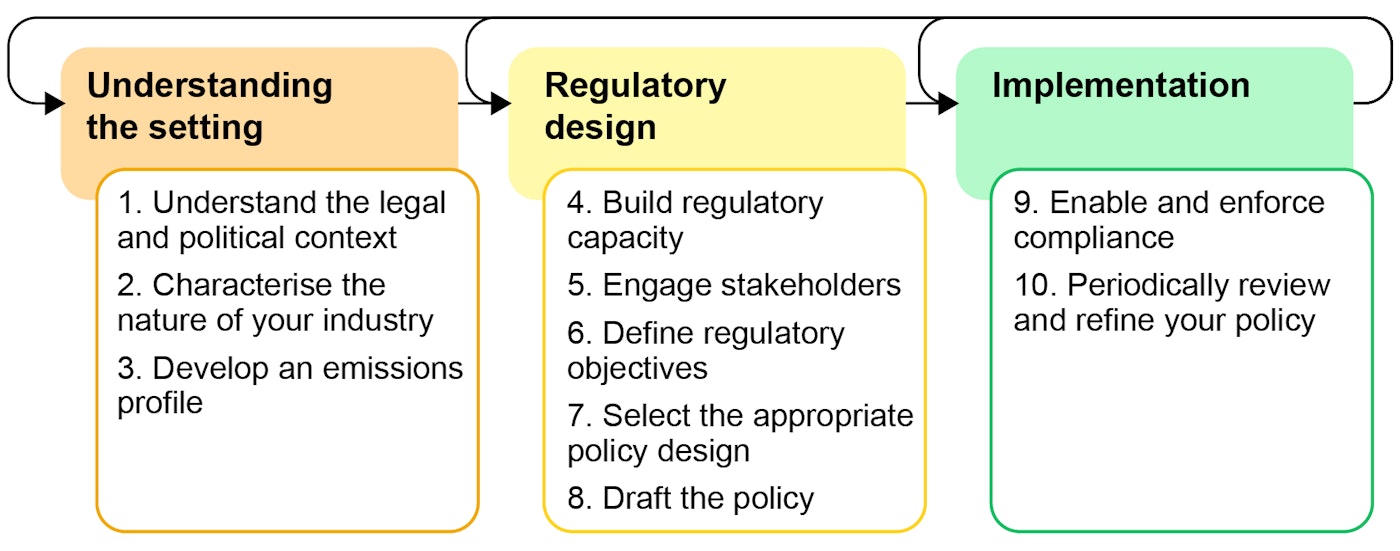

One of the aims of any new policy effort should be to improve measurement and reporting of emissions data, which can in turn lead to more efficient regulatory interventions. However, the current state of information on emissions should not stand in the way of early action on methane abatement. Experience shows that countries can take an important “first step” today based on existing tools, which may include prescriptive requirements on known “problem sources” combined with monitoring programmes that seek to detect and address the largest emissions sources (“super emitters”). In terms of process, implementing a new policy or regulation should involve three distinct phases, each covered in detail in this roadmap: understanding the local setting and circumstances, regulatory design and development, and finally, implementation.

Online table of contents

Download translations

The case for methane regulation

Reducing methane emissions from oil and gas operations is among the most cost-effective and impactful actions that governments can take to achieve global climate goals. What’s more, a growing number of jurisdictions recognise that regulatory action plays an important role alongside voluntary industry action.

Action is needed on methane

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with important implications for climate change. Although methane has a much shorter atmospheric lifetime than carbon dioxide (CO2) – around 12 years, compared with centuries for CO2 – it absorbs much more energy while in the atmosphere. Thus, while methane tends to receive less attention than CO2, reducing energy-sector methane emissions will be critical for avoiding the worst effects of climate change.

The IEA estimates that the oil and gas sector emitted around 70 Mt of methane (approximately 2.1 Gt CO2-eq) in 2020 – just over 5% of global energy-related greenhouse gas emissions. Early satellite data suggest that the incidence of large-scale leaks fell in 2020, although some of this likely stems from the major drops in production as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. Under the IEA Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS), emissions from this sector will need to fall to around 20 Mt per year by 2030 – a drop of more than 70% from levels in 2020.

Oil and gas sector methane emissions, historical and in the Sustainable Development Scenario, 2000-2030

OpenThis 70% reduction coincides with the amount that would be technically possible to abate, according to the IEA Methane Tracker. In addition, a significant share of these emissions can be abated at no net cost, because the value of the captured methane is sufficient to cover the cost of the abatement measure, i.e. there should already be an economic incentive to avoid the release of this gas to the atmosphere. The precise share of emissions that can be avoided at no net cost will undoubtedly vary from year to year and from region to region, with the prevailing gas price being a key variable. Natural gas prices in 2020 were a lot lower around the world than in previous years, so the share of abatement that pays for itself is lower than in previous years. But it will pick up again as natural gas prices rise.

There are a number of voluntary, industry-led efforts to reduce methane emissions, and a number of individual companies have announced methane reduction targets in the past year. Nevertheless, an immediate and significant change in ambition is needed to achieve the sorts of reductions that would be consistent with international climate objectives. While industry efforts can and should continue, government policy and regulation will be critical to removing or mitigating obstacles that prevent companies from getting started and going further.

Barriers to voluntary action

The IEA’s country-specific methane cost curves suggest that a significant number of abatement measures would pay for themselves, provided that the captured gas can be delivered to market and sold at the going market rate. Although this simple cost analysis suggests that companies should be willing to undertake some of these actions voluntarily, this is not necessarily the case in practice. Understanding what prevents companies in different countries and market contexts from undertaking actions that appear to be cost-effective is a vital starting point in the design of a regulatory approach to methane abatement.

There are three main types of barrier that explain why companies are not taking full advantage of these opportunities: information, infrastructure and investment incentives.

Information

There is a significant information gap in many companies about methane, regarding both its environmental impacts and, more specifically, the level and sources of emissions from company operations. There is also a lack of awareness in many cases about the abatement technologies that exist, their costs, and the benefits of capturing and using or selling gas that would otherwise be emitted. Even if senior management is aware of the risk of methane releases, this may not be reflected in the broader company culture and its operating practices so that the personnel on the ground, who are in a position to take action, are not doing so. Often this lack of information is an oversight; however, existing policies may also create a disincentive to obtaining full knowledge. For instance, in a jurisdiction that charges emitters a fee or tax based on volume of pollution emitted, companies may fear raising their compliance costs if they discover new sources of methane.

Infrastructure

In many cases, captured gas can be easily brought to market. However, in other cases, particularly where gas is co‑produced (or “associated”) with oil, existing pathways or businesses may not exist to bring the gas to productive use. In these cases, it may be necessary to construct new infrastructure to bring the gas to a consumer, including new compression equipment, gathering pipelines and transmission pipelines, or liquefaction facilities. Methane abatement may falter without policies that require or incentivise productive use of natural gas.

Investment incentives

While context matters for corporate decision-making, all firms have limited capital to deploy. Thus, opportunities to invest in methane reduction must compete with other investment opportunities. Even where abatement is cost-effective, companies may opt to direct capital towards investments where a higher rate of return is possible. Moreover, abatement may seem less cost-effective as long as the environmental costs of pollution are not factored into the investment calculation. In addition, where the owner of the gas is not the owner of transmission infrastructure, there may be an issue of “split incentives,” whereby the pipeline company that pays to repair leaks sees the benefits accrue to the owner of the gas, from additional throughput. Finally, state-owned firms may not directly benefit from cost-saving measures because they return earnings to the government treasury, and then receive pre‑determined appropriations to cover operations.

What can governments do to drive methane reductions?

Governments can address many of these barriers with policy and regulatory tools. If information poses a barrier, policies could include educational strategies, such as trainings; certificate programmes for workers; measures on monitoring, reporting and verification of emissions; reference to international voluntary corporate reporting standards; or initiatives to encourage knowledge-sharing and best practices. With respect to infrastructure, governments might introduce requirements in the planning stages of projects, directly invest in building new infrastructure or adopt policies that allow spreading of the development costs across multiple firms and end users. Governments may also be able to price environmental externalities or create financial incentives for onsite use of captured gas, expenditures in abatement technologies, or repair transmission equipment to remove barriers to investment.

The aim of these interventions is twofold. First, they can unlock the abatement measures that are already economically advantageous today, i.e. the methane leaks that can, in our view, be abated at no net cost. Second, they can facilitate and encourage actions that address the range of methane emissions that are technically possible to abate, i.e. the 70% reductions that are achieved in the Sustainable Development Scenario by 2030. To reach this level, it will not be enough to simply remove the barriers that prevent companies from acting on their own. Broader regulatory initiatives also have an important role to play. Firms are increasingly recognising this and are expressing interest in “sound methane policies and regulations that incentivise early action, drive performance improvements, facilitate proper enforcement, and support flexibility and innovation.”1

Regulations calibrated to each jurisdiction’s specific goals will be critical to ensuring that companies undertake the appropriate abatement actions alongside voluntary action by companies. There are many types of regulations, but what they all have in common is that they can fundamentally change the cost-benefit analysis for firms and drive them to internalise the societal cost of that pollution.

A Regulatory Roadmap and Toolkit

This report aims to provide a complete “getting started” guide for policy makers looking to develop new regulations to tackle oil and gas methane emissions within their jurisdictions. This guide consists of two companion pieces: a Regulatory Roadmap and a Regulatory Toolkit.

The Roadmap focuses on the process of establishing a new regulation. It details ten key steps in developing a new regulation and provides a step-by-step guide to aid regulators in gathering the information they need to design, draft and implement an effective regulatory scheme.

The Toolkit focuses on the content of methane regulations. It characterises the different regulatory approaches that are currently in use for methane, with appropriate links to the IEA Policies Database for specific examples. The aim of the Toolkit is to provide regulators with an encyclopedia of the different regulatory tools that are available to them as they craft new policies.

How can governments design and implement new regulations?

The IEA has identified ten steps that will assist regulators in selecting a regulatory approach and implementing a set of effective methane policies that match the local situation. Although presented sequentially here, these steps may be carried out in a different order, may take place concurrently, or may even be repeated once new data on emissions or new technologies become available.

A ten-step roadmap for policy makers

Step 1: Understand the legal and political context

Step 2: Characterise the nature of your industry

Step 3: Develop an emissions profile

Step 4: Build regulatory capacity

Step 6: Define regulatory objectives

Step 7: Select the appropriate policy design

Step 9: Enable and enforce compliance

Step 10: Periodically review and refine your policy

Across these steps, the process of implementing a new regulation unfolds in three distinct phases. The first phase takes place before any formal development of a regulatory proposal. It consists of an information-gathering exercise designed to equip policy makers with an understanding of how best to match policies and regulations to the institutional circumstances, existing regulatory framework, market context and emissions profile of the jurisdiction. This information-gathering phase corresponds to the first three steps of the Roadmap.

Once policy makers have gathered this information, the next phase involves designing and developing the regulatory proposal, taking care to enhance institutional capacity and engage with internal and external stakeholders. This regulatory development phase corresponds to Steps 4 through 8 of the Roadmap. At this stage, regulators should also consider the examples of different regulatory approaches that are collected in the Toolkit.

Even after a regulation is published, a great deal of work remains to ensure that it operates effectively. In the implementation phase, policy makers will need to assure compliance with requirements and develop a plan to update the regulation as needed. This corresponds to Steps 9 and 10. Note that although implementation does not begin until a regulation is finalised, policy makers should consider these steps at the drafting stage to build in compliance assurance and adaptive strategies from the start.

Cycle of key regulatory steps

Open

What policy and regulatory tools are available to regulators?

A growing number of jurisdictions have already recognised that regulatory action plays an important role in driving these actions in the oil and gas industry. Some governments have taken action; others have pledged to follow in the coming years. From our survey of early actions, we have developed a typology of regulatory approaches designed to demystify the complex web of regulations that exists in many countries. An introduction to this typology is outlined below, and the Toolkit section of this report provides specific examples for each approach.

Typology of regulatory approaches

The regulatory approaches that have been applied to methane can be categorised into four main types of regulatory approaches:

- prescriptive requirements,

- performance-based or outcome-based requirements,

- economic instruments and

- information-based requirements.

The table below illustrates each regulatory approach by describing its application to the replacement of “high-bleed” pneumatic controllers. These controllers, used for a variety of purposes across the oil and gas value chain, can represent a significant share of the industry’s methane releases. For instance, according to the US greenhouse gas emissions inventory, emissions from these pieces of equipment represented about 25% of methane emissions from petroleum and natural gas systems in the United States.2

Regulatory approaches applied to pneumatic controllers

|

Regulatory approach |

Definition |

Example |

|---|---|---|

|

Prescriptive |

Prescriptive instruments direct regulated entities to undertake or not to undertake specific actions or procedures. |

Operator is directed to replace pneumatic controllers with lower-emitting controllers by a certain date. |

|

Performance- or outcome-based |

Performance-based instruments establish a mandatory performance standard for regulated entities but do not dictate how the target must be achieved. |

Operator is directed to achieve facility-wide methane reductions from a baseline. The operator then decides to replace the highest-emitting controllers because it is most cost-effective to target these pieces of equipment to meet the overall target. |

|

Economic |

Economic instruments induce action by applying penalties or introducing financial incentives for certain behaviours. This may include taxes, subsidies, or market-based approaches such as tradable emissions permits or credits. |

Operator must pay a pollution tax for emissions. Alternatively, the operator may deduct the costs of replacing high-emitting equipment from its tax liabilities. Under either scenario, the operator may choose to replace the controller for financial reasons. |

|

Information-based |

Information-based instruments are designed to improve the state of information about emissions, and may include requirements that regulated entities estimate, measure and report their emissions to public bodies. |

Operator is directed to report emissions of known high-emitting equipment or activities. In view of the volume quantified, the operator may choose to reduce rather than disclose emissions associated with pneumatic controllers. |

Most jurisdictions with methane-specific oil and natural gas regulations have relied heavily on prescriptive requirements to achieve emissions reductions. This “command and control” approach focuses on directing the installation or replacement of specific pieces of equipment. For example, if a jurisdiction determines that many of its routine emissions come from “high-bleed” pneumatic valve controllers used across the oil and natural gas value chain, a prescriptive rule could direct operators to replace existing controllers with “low-bleed” or “no-bleed” alternatives, and prohibit installation of high-bleed equipment at new facilities.

Prescriptive methane policies in selected producing countries

National policies Provincial/state-level policies only

Definitions for each type of instrument can be found in the Policy Type Definitions section of this report. This table reflects entries in the IEA Policies Database as of 18 January 2020. We welcome feedback from jurisdictions regarding any updates to existing policies or on additional policies that are missing from the database.

By contrast, performance- or outcome-based requirements require firms to meet a specific emissions target for a specific piece of equipment or facility, but they do not specify how the firm must meet that target. For example, Mexico’s 2018 regulation requires operators of existing facilities to establish and achieve six-year emissions reduction goals for each facility. Operators required to reduce emissions will look for the most cost-effective repairs and replacements across each facility. If some “high-bleed” controllers are contributing heavily to the overall emissions profile of the facility and can easily be replaced, operators will replace these controllers.

Performance-based methane policies in selected producing countries

National policies Provincial/state-level policies only

Definitions for each type of instrument can be found in the Policy Type Definitions section of this report. This table reflects entries in the IEA Policies Database as of 18 January 2020. We welcome feedback from jurisdictions regarding any updates to existing policies or on additional policies that are missing from the database.

Some jurisdictions may opt to use economic instruments that deploy penalties or incentives to induce action. The simplest form of economic regulation would be a tax on emissions of methane. For the given example, this would in essence encourage a firm to “replace valve controllers or pay for the methane that they emit.” In response, an operator might prefer to replace the higher-emitting controllers rather than pay a methane tax. Norway’s carbon tax, which covers methane emissions from offshore oil and gas facilities, represents this approach.

In contrast to policies that assess a penalty of sorts for emitting methane, a government may offer inducements or economic incentives to encourage abatement. An incentive rule might state, “If you replace a valve controller, you can deduct the cost of the replacement from the royalties owed to the state.” For example, Nigeria allows companies to deduct capital expenditures on equipment to capture associated gas from its profits, and to deduct royalties assessed on associated gas that is sold and delivered downstream.

Economic methane policies in selected producing countries

National policies Provincial/state-level policies only

Definitions for each type of instrument can be found in the Policy Type Definitions section of this report. This table reflects entries in the IEA Policies Database as of 18 January 2020. We welcome feedback from jurisdictions regarding any updates to existing policies or on additional policies that are missing from the database.

One of the biggest hurdles to effective regulation of methane from the energy sector is the extent of uncertainty – about the magnitude of emissions, emissions sources and variability. Given this, a particularly fruitful approach might be information-based requirements. A rule might require firms to “tag all high-emitting valve controllers and submit monthly reports on their emissions.” For some operators, this may provide new insight into the magnitude of their emissions. Once they learn how much they are emitting, they may take voluntary action. If these emissions reports must be made public, this may also give rise to pressure on operators to reduce emissions from external stakeholders.

Information-based methane policies in selected producing countries

National policies Provincial/state-level policies only

Definitions for each type of instrument can be found in the Policy Type Definitions section of this report. This table reflects entries in the IEA Policies Database as of 18 January 2020. We welcome feedback from jurisdictions regarding any updates to existing policies or on additional policies that are missing from the database.

Many examples of these regulatory approaches are already in place. This guide relies heavily on these examples, drawn from the IEA Policies Database and categorised according to standardised Policy Type Definitions, in order to point regulators to real-world examples of these existing policy tools and related resources. These examples should be a primary resource for regulators following this guide, providing a source of inspiration and illustrating best practices.

Key insights for policy makers

Policy makers that have already established methane regulations have learned a great deal. This guide seeks to share those best practices and lessons learned in order to maximise the effectiveness of new regulations.

Policy and regulation can help countries meet emissions goals

Policy makers should not assume that the industry has the right incentives to stimulate voluntary action sufficient to address the methane problem. As noted above, a growing number of jurisdictions have recognised the importance of sound policy and regulation alongside voluntary action by industry. Even if industry may take some action on its own, not all of the necessary reductions will be cost-effective on their own, and policy and regulation can work to fundamentally change company incentives in this regard.

There are no one-size-fits-all solutions

A policy and regulatory regime will be most effective if it is tailored to a jurisdiction’s local situation, including the political and regulatory context, the nature of the industry, the size and location of emissions sources, and the jurisdiction’s policy goals. Different regulatory approaches have particular advantages and disadvantages that depend on circumstances that will vary across jurisdictions, and policy makers should take the time up front to understand how these circumstances play out within the local context. The steps outlined in the Roadmap are designed to help regulators understand these circumstances and make decisions on which approaches fit their situation best.

Better information can enable more efficient regulatory requirements

Performance-based requirements and economic instruments can produce more economically efficient outcomes by enabling an operator to identify the most cost-effective abatement options. However, these approaches often require a robust measurement and reporting regime to function properly. For instance, a methane tax cannot be effectively enforced if no one knows how much methane is being emitted. Developing and implementing a robust measurement and reporting regime may take several years. For jurisdictions in the early stages of regulating methane, prescriptive standards may be the best option until a robust measurement and reporting regime is in place.

However, countries do not need to wait for better data to take action

Fortunately, prescriptive requirements can be effective at reducing emissions in their own right. Moreover, they can serve as a useful first step on the path to more flexible and economically efficient regulations because they are relatively simple to administer and do not require an accurate baseline understanding of the level of emissions or a robust measurement and estimation regime. Therefore, a starting point for jurisdictions regulating methane for the first time might be to combine prescriptive requirements on known "problem" sources with a monitoring programme that detects "super‑emitters" using satellite or inspection data and requires companies to address them as they arise. Over time, it may be possible to incorporate aspects of other approaches into a primarily prescriptive regime, such as broad facility or company level targets that complement other requirements.

Critically, this path is well worn. Policy tools adequate to address methane emissions already exist, in one form or another. Regulators following this guide and drawing on the different resources available will be equipped with the information needed to decide among the available approaches, and ultimately, to execute that vision.

How to use this guide

This guide is divided into two main components, the Roadmap and the Toolkit. The Regulatory Roadmap treats in detail each of the ten steps highlighted above and identifies key considerations and decision points for each step. The steps are presented sequentially, but will generally prove to be modular, with feedback loops and iterations between different stages of policy making. Feel free to focus on the steps that you have greatest interest in and skip steps that you have already mastered.

Next, the Regulatory Toolkit presents different elements of policy making to support regulators throughout the policy development and implementation phases. It discusses general regulatory strategies, providing further detail on the four general regulatory approaches described above and illustrating their use through examples of current methane regulations. As with the Roadmap steps, each topic is intended to be modular and stand-alone, and you may wish to refer to aspects of the Toolkit as you walk through the Roadmap steps.